“I would like to see the sky machine on every corner instead of the Coke machine. We need more skies than Coke.” – Yoko Ono, 1966.

Growing up the daughter of proud, British baby-boomer parents, the name Yoko Ono was not exactly revered in my household. In fact, she was considered a weird, controlling creature that somehow brainwashed John Lennon and systematically broke up the Beatles—the greatest rock and roll band of all time (according to my father). It wasn’t until art school that I began to learn who Ono really was and why she is considered one of the most iconic and mythological people in contemporary society.

Yoko Ono has been in the public eye for over 50 years, and she has been viewed as a muse, destroyer, widow, mother and artist. Granted, the fact that she is a household name is due largely to her late husband’s fame and legacy. However many are not aware of the her own accomplishments, innovations and her impact on the contemporary art world, beginning before her much publicized marriage and continuing until today.

Yoko Ono was born in Japan in 1933 to wealthy parents. Her family experienced much hardship during the Second World War, surviving the great fire bombings of Tokyo in 1945. They lost everything and were forced to beg and barter for food, which Ono credits as being the inspiration behind her imaginary/instructional art works or, as she refers to them, “paintings for the mind.”

After the war her family settled outside New York City, where Ono studied at the prestigious Sarah Lawrence College. In New York she began visiting galleries and art “happenings” (a form of performance-art involving the participation of both artist and audience), and these experiences inspired her own emerging work. In the early 1960s Ono was closely associated with the Fluxis movement, which was more a state of mind than a style of art. Members valued social goals over aesthetic goals and their main aim was to upset bourgeois (ie: middle-class or materialistic) routines of art and life.

The Fluxus incorporated influences from Dadaist theory, a school that originated in Europe after the First World War when founding artists Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and Jean Arp felt they could no longer trust reason and the established order of things. The intent of Dada artists was to denounce all previous attitudes and perceptions and to shock the audience. Similar to Dada and often described as anti-art, the Fluxis used mixed-media, mail art, actions and happenings to promote a new culture of performance-based, audience-interactive, and non-commodifiable art.

One of the most iconic pieces of performance art, and the one for which she is most renowned, is Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” (c. 1964). Performed on several occasions and in a variety of venues, “Cut Piece” featured Ono alone on a stage, dressed in a black garment. Volunteering audience members were given scissors and invited to cut pieces from her dress. Like most performance-based artists, Ono could not have had a set purpose when she performed this work—or if she did it would be pointless—because it depended on the audience/viewer response and action.

For the most part, people were at first hesitant to come on stage, but as they lost their inhibitions participants began to cut bigger and bigger pieces of cloth until the dress was left in shreds (in one performance a young male actually cut off her undergarments).

Depending on where she performed “Cut Piece,” Ono received a different reaction. In Japan the audience was shy and hesitant. In London they became so violent security had to intervene. But even if no one had come forth to snip the dress, the performance would still have made a statement.

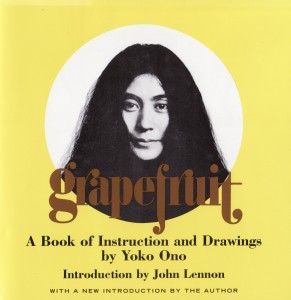

This is the strongest, most encompassing element of Ono’s catalogue as a whole: its participatory aspect. Everything she has done has been dependent on her audience or viewer. Her book Grapefruit is an excellent example of this. It contains instructions on how to perform her various imaginary pieces, such as “Painting to be constructed in your head,” and “Conversation piece.” In one of my personal favourites, “Painting for the wind,” the reader is instructed to “cut a hole in a bag filled with seeds and place the bag wherever there is wind” (1961, summer).

It is impossible to discuss Yoko Ono’s work without mentioning her late-husband and collaborator, John Lennon. After their extremely public romance and marriage, Ono found she was somewhat shunned or distanced by the contemporary arts community. But the couple decided to exploit their massive profile to forward their social agenda for peace. On their honeymoon, the two staged a “Bed-in for Peace” in Montreal, knowing the media would eagerly cover something so curious and provocative. John articulated his understanding of the potential of modern media very well; he knew that whatever he and Yoko did would end up in the papers.

“We decided,” he said, “to use the space we would occupy…with a commercial for peace and also for a theatrical event.” Life as art with social goals: very Fluxis.

After Lennon’s devastating assassination in 1980, Ono continued to manage his estate and advocate for world peace, eventually getting back to conceptual art in large galleries. Most recently she has exhibited and performed commemorative shows in honour of the 40th anniversary of “Cut Piece.”

In the movie “Imagine: John Lennon,” Lennon describes how he met his wife: “Yoko was having an art show at the Indica Gallery…I went down the night before the opening. The first thing that was in the gallery was a white step ladder and a painting on the ceiling and a spy glass hanging down. I walked up this ladder and I picked up the spy glass and in tiny little writing it just said, ‘Yes’…” Lennon also once referred to his wife as the world’s “most famous unknown artist. Everybody knows her name but nobody knows what she does.” For the Silo, Eve Yantha.

For further contemplation:

Imagine: John Lennon- A startling film derived from over 200 hours of John’s own film and video footage, as well as stills & heretofore unpublished music from John and Yoko’s personal collection. (1988)

Grapefruit: A Book of Instruction and Drawing by Yoko Ono (c. 1964; 1970)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.